Personal technology devices. Online delivery services. Life insurance. Even gas and oil… Technically speaking, all of these items and services are optional; although we might not enjoy the resulting lifestyle changes, we could live without them.

What isn’t optional? Food.

Two major consequences derive from our dependence on food and agriculture. First, food and agriculture are enduring markets. Though perhaps not as lucrative or thrilling as Big Tech investing, agriculture and farmland are not going away any time soon. Historically, the farmland market has been generally resistant to market fluctuations of boom and bust economic cycles. Farmland is an alternative investment, like traditional real estate in office or multifamily buildings, that provides unique opportunities for diversifying investment portfolios given its low correlation to traditional stock and bond portfolios. Today, however, there are limited options in public, liquid securities markets to invest in farmland.

Secondly, food is non-negotiable for human survival. Therefore, as a species, we have a philanthropic responsibility to ensure that all people have reliable access to nutritious food. Investing in agriculture, food distribution, and land improvement is not only economically rational but ethically impactful.

Food Security

World hunger— the phrase often conjures images of malnourished residents of Third-World countries. Tragically, hunger is a major issue not only in developing countries but even in highly industrialized nations. 1 in 9 Americans suffers from food insecurity, defined by the USDA as “limited or uncertain access to adequate food.” This means that 26 million adults and 11 million children lack reliable access to nutritious food in the US alone. Those figures suggest systemic problems and perhaps endemically poor allocation of an abundant resource.

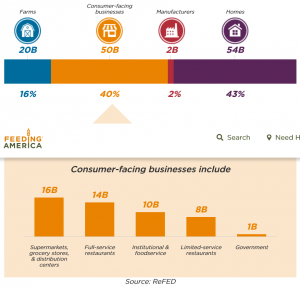

COVID-19 has only worsened the food insecurity crisis. Northwestern researchers estimate that 23% of all American households and 30% of US households with children experienced food insecurity in the past year. In a nation where annual food waste in family households totals 54 billion pounds, manufacturers and restaurants throw away 52 billion pounds of food, and 20 billion pounds of food grown is left to decay in farm fields, food waste and insecurity are unacceptable byproducts of inefficiencies in our modern, technologically advanced society.

An illustration of annual food waste in America

The issue, clearly, is not an inadequate supply of food; the US produces enough food to nourish every single American. Instead, distribution is the primary challenge: how do we ensure that food is efficiently and compassionately apportioned? To solve this question, we must first understand food flow networks.

Food Flow Networks

Food flow networks, or interconnected food supply chains, map the often winding and unpredictable path that food travels from farm to table. Certain foods follow a straightforward route—milk, for instance, is first bottled, then pasteurized. Afterwards, it is shipped to distribution centers and then transported to supermarkets. The same milk, however, could take a more circuitous path, perhaps being converted into cheese, powdered milk, or yogurt. Each of these dairy products could be packaged and distributed alone or as an ingredient in other processed foods.

Food flow networks not only outline the steps in the distribution process but also consider geography. Where food is produced, the distance it travels, and where it ends up are critical logistical elements to maximizing food security.

Food Production

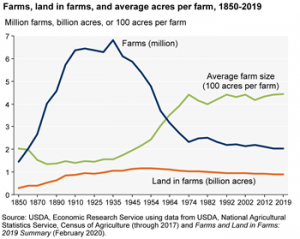

The top ten crop-producing states are California, Iowa, Nebraska, Texas, Minnesota, Illinois, Kansas, Wisconsin, North Carolina, and Indiana. Together, they account for nearly 55% of US crop sales. This concentration reflects these state’s weather and topographical endowments and the trend toward larger farms—as the size of the average American farm increases, the total number of farms has been decreasing. Consequently, the percentage of farmland operated by small-scale farms is decreasing. The graph below illustrates the evolution over time from small, primarily subsistence farms to larger, primarily industrial farms.

Size and number of farms from 1850 to 2019

US policy safeguards the strategic aspects of our nation’s food supply and so may favor large, wealthy farms over their smaller counterparts. According to the Heritage Foundation, commercial farms, 10% of all farms in the US, received 73% of commodity payments and 83% of crop insurance indemnities in 2016. Small family farms, the remaining 90% of US farms, received only 27% of commodity payments and 17% of crop insurance indemnities that same year.

Farm concentration is highly controversial. Supporters assert that industrial agriculture increases efficiency and output. Critics from across the political spectrum, however, argue that industrial farming impoverishes rural communities, damages the environment, and harms consumers.

This controversy should be viewed in light of facts rather than emotional appeals and generalizations. Despite its imperfections, the modern agriculture system certainly has improved in efficiency and output. According to John Deere, 83 hours of labor and 2.5 acres of land were required to produce 100 bushels of corn in 1850. As of 2016, only 2 hours of labor and 0.6 acres of land were necessary. Moreover, despite concerns about environmental harm from farming, recent technological advances allow farmers to decrease pesticide, fertilizer, land, and water usage. Sustainable and organic farming technology, still a budding field, benefits environmental and community health and lowers food prices for consumers. More on this nascent, sustainably-focused competition to industrialized farming may appear in future articles.

Food Processing

After food is harvested, it is taken to be processed. Like farming, food processing is growing more concentrated. Food processing facilities, largely located in California, New York, and Texas, are increasing in size, while food processing companies are likewise consolidating.

Companies also increasingly employ vertical integration, the practice of controlling multiple steps in the food production process. For instance, a beef company might own cattle-breeding facilities, feed mills, slaughterhouses, and processing plants. Once again, consolidation and integration are controversial and complex trends. Much like other U.S. sectors such as healthcare, certain elements of the U.S. agricultural and food chain have pursued efficiency and have concentrated operations to such an extent that the system has no redundancies and lacks resiliency should their operations be disrupted.

The COVID pandemic illustrates these difficulties. When just a few large groups lead the agriculture and production markets, a disturbance in any producer disrupts the food supply for many consumers. Thus, COVID outbreaks in meat-processing plants forced farmers to euthanize 2 million chickens and 300,000-800,000 pigs, while variations in consumer demand left the food supply chain spluttering. To avoid future food supply disruptions, the food network of the future must balance efficiency and redundancy, large industrial farms to promote food security in commodity-type products like corn, soy and wheat and small, niche community farms for organic or fresh “farm to table” quality products like fresh vegetables, fruit, and nuts.

Distribution

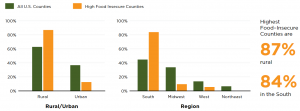

Finally, food flow networks culminate with distribution to consumers. Numerous factors influence food distribution. Businesses consider not only population and location but socio-economic conditions as well. Consequently, low-income and sparsely populated areas face unreliable food supplies. According to Feeding America, 64% of the least food secure counties face exceptional poverty. Regionally, rural counties are disproportionately food insecure, and the South is the least food secure area. Significant racial disparities also exist, with minorities facing food insecurity at alarming rates.

Rural versus urban and regional food insecurity in America

Many highly food-insecure areas are categorized by the USDA as “food deserts,” places where adequate, nutritious food is not readily accessible. NPR reports that 19 million Americans live in food deserts. Several large grocers and retailers, such as Walmart and dollar stores, have attempted to fill this gap. The chains’ entrance into food-insecure areas, however, is controversial—these large companies can undercut local grocers, causing more concentration in the local food market. Meanwhile, dollar stores, with appealing price tags (though high unit costs), generally supply processed foods rather than nutritious produce. Unfortunately, the prevalence of processed foods reinforces the tragic link between poverty and obesity.

Strategies and Solutions

Opportunities to combat food insecurity exist at all levels of the food flow network. Servant Financial is presently focusing its resources on potential investment opportunities in a “barbell” of impact. First, we are investing in productivity improvements at the start of the food chain on the farm. Second, we are exploring innovative investments in food distribution infrastructure to serve those communities with the greatest food insecurity: food deserts. We believe this two-part investment approach will improve food production and ultimately mitigate the effects of poverty and food insecurity at the consumer level.

Farmland Improvement

Farmland improvement targets the very roots of the food flow network. Investing in farmland enhances food quality and supply as well as human and environmental wellbeing. As noted above, farms are rapidly consolidating—large, industrial farms are gobbling up their smaller counterparts. The economics of highly mechanized farming and the need for scale to spread the fixed cost of the equipment over more acreage make it very difficult for very small farms (sub 100 acres) to succeed unless they simply become a farmland owner and lease the farm to a scaled operator. This behind-the-scenes operational consolidation has been occurring across multi-generational landholding and farm-operating families for decades.

Investing in farmland in Qualified Opportunity Zones (QOZ) seeks to improve the productive capacity of farmland and create jobs and economic benefits to rural American communities. QOZs are designated economically-challenged regions in which investment is encouraged by preferential tax treatment. Investors can defer capital gains taxes rolled into a QOZ until the earlier of 2026 or as long as they hold the investment. Additionally, investors benefit from a 10% exclusion of the capital gain deferred if they maintain the investment for at least five years. Further, if the taxpayer holds a QOZ investment for 10 years there is a permanent exclusion on the appreciation of their investment.

Farmland improvement in QOZs revitalizes small farms in struggling regions. Investments take various forms, from improving water drainage, to building new grain storage, to enhancing irrigation systems, to improving soil quality, to developing renewable power generators and adjacent energy storage. Ultimately, these investments impact farmers, who benefit from farming productivity improvements and increased profits; laborers, who experience greater job security; and consumers, who have more reliable access to locally-grown food. Indeed, the benefits continue, as investing in farmland in QOZs may even be supportive of sustainable and organic farming practices. Stay tuned for more information on Promised Land Opportunity Zone Fund I, LLC’s farmland investment activities and its strategic alliance with Farmland Partners.

Food Banks and Pantries

Food banks and pantries address hunger directly by serving food-insecure families. Food banks are depositories that store large quantities of food. Items are transported from food banks to food pantries, local centers generally run by community-based not-for-profits which distribute food to individuals.

Most items in food banks and pantries are donated by individuals and businesses. Farms, restaurants, and grocery stores often have more food than they can sell. By redirecting this supply to food banks, businesses not only nourish our communities but combat the massive systemic food waste outlined earlier. Federal programs, too, supply food banks by purchasing items from farmers. In 2020, such USDA programs provided 1.7 billion meals. Finally, food banks and pantries can purchase food themselves with donated money.

Despite their noble goal, food banks do face some criticism. Because they are often volunteer-run, food banks usually operate on a limited schedule. Reliant on donations, many food banks offer a limited selection, often lacking in fresh dairy and produce. The overall quantity and variety of food available at food banks can be low. Yet another dilemma is the stigma surrounding food pantries: many people who utilize food pantries experience feelings of shame and alienation and complain of unpleasant atmospheres. Unfortunately, this stigma discourages food bank use. A 2018 study among food-insecure college students revealed that stigma was the main obstacle to food pantry utilization.

In spite of these drawbacks, food bank use increased during the pandemic. Along with unemployment rates, the demand for food banks and pantries soared. Since March 2020, distribution by US food banks has grown by about 55%. Sadly, nearly 40% of food pantry patrons at the beginning of the pandemic were first-time users.

Increasing demand as well as criticisms of food pantries provide opportunities for improvement. One especially creative pantry network is the Greater Chicago Food Depository, or GCFD. GCFD recently provided grants to community not-for-profits to open four new pantries, which, when complete, will resemble traditional grocery stores. GCFD aims to facilitate the creation of pantries more responsive to community needs and desires. For instance, one community-based not-for-profit working with GCFD plans to accept feedback on food selection and to implement an online order and delivery service.

Patrons visit a GCFD food pantry during the pandemic

GCFD wants the pantries to be more than food distributors. They envision a pantry that is also a community center. Patrons will be able to enjoy a cup of coffee; participate in exercise, cooking, nutrition, and budgeting classes; send their children to extracurricular programs; and shop for food in one convenient, attractive space. Visiting these revitalized food pantries will not be dreary: it will be uplifting.

One successful, large scale community-based food security operation with limited publicity are the 138 bishop’s storehouses run by the Mormon Church. The bishop’s storehouse system is a network of church-owned and -operated commodity resource centers. They function much like cashierless retail grocery stores, such as Amazon Go, but with a philanthropic wrinkle: goods cannot be bought at storehouses. Instead, they are distributed to needy individuals under the direction of church leaders.

The storehouses stock basic food and essential household items, produced largely from Mormon-owned agricultural properties, canneries, and light-manufacturing operations. The entire system is vertically integrated from farming and harvesting through processing and distribution.

Needy recipients are invited to work or render service in various ways in exchange for goods. This reciprocal exchange helps maintain the personal dignity and responsibility of the recipients, who do not view the food solely as a handout. All storehouse work is performed by volunteers. The contribution of time, talents, and financial resources sustains the storehouse and the fabric of the community at large.

Yet another instance of innovation is Feeding America’s free-market approach to improving the efficiency of food distribution to its network of food banks and pantries. Previously, Feeding America treated all food as interchangeable from an allocation and distribution perspective. Shipments to individual food banks were measured by weight rather than by nutritional variety and composition. Hindered by this defective central planning, Feeding America struggled to allocate food rationally and fairly. For instance, Feeding America sent loads of potatoes to Idaho food pantries, where locally-grown potatoes were bountiful. Meanwhile, food pantries in Alaska, short on potatoes, received an excessive supply of pickles.

Seeking to improve, Feeding America consulted University of Chicago economist Canice Prendergast. Prendergast realized that Feeding America’s central planning was hampering their efforts. The large, central organization lacked specific, local knowledge about the supplies and needs of individual food banks. To address this issue, Prendergast advocated a free-market approach to resource allocation. Feeding America created its own internal currency; the neediest food banks receive the largest amounts of “money,” while better-off food banks receive less currency. Using this money, individual food banks bid for shipments of food on an online platform. Food banks can also save up their money so they can bid more aggressively on particularly needed items. For instance, a bank might save its shares to purchase a large supply of peanut butter, a valuable food pantry favorite. Meanwhile, the prices of fresh produce and dairy generally stay lower because these perishable goods must be used immediately. Using this system, food banks in Feeding America’s network receive supplies that they and their customers desire and need.

Volunteering is not the only means of revolutionizing food pantries. With reimagination comes the opportunity for investment. Long-term, low-interest loans allow nonprofits to open or improve food banks and pantries. Investors can also give short-term bridge loans, or grants much like GCFD, to provide nonprofits with much-needed capital to improve their infrastructure. These investments can be risky but rewarding: food pantries ultimately improve the health and wellbeing of our communities.

To win the battle against malnutrition and food insecurity, we must address both food production and distribution. Investing in farmland improvements and community-based food storehouses are just two possible areas of innovation in the food network that we are cultivating. The ultimate purpose of investing in farms and food distribution is not in the production and consumption functions but in sustaining the future of humanity. Contact Servant Financial to learn more about investing with purpose in food and agriculture.