From fruit to baked goods, burgers to craft beer, organic is in. In 2016, 82% of Americans reported purchasing organic food. From 2010 to 2018, the organic market grew at least 5 percent annually, and researchers forecast that this incredible growth will only continue. But what is organic food? And is the premium cost really worth it?

Organics Overview

American-grown organics are certified by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) following a complex set of regulations. Overall, organic farming maximizes natural methods—employing animal or green manures, crop rotation, cover crops, and open grazing, for instance—and limits synthetic methods, including genetic engineering and artificial soil treatments. The details of the intricate balance between natural and synthetic, however, are complicated. For instance, an organic product cannot contain any genetically-modified organisms, or GMOs; however, certain synthetic fertilizers may be used for prescribed purposes in limited amounts. Organic livestock may receive chemical vaccinations; however, the administration of drugs to organic livestock is severely limited.

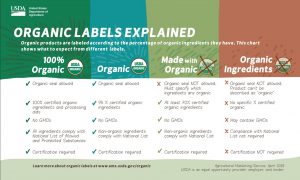

Ultimately, crops and fresh produce with the USDA organic seal must be grown on soil free from prohibited substances for at least three years. Organic meat is produced from livestock free from hormones and antibiotics, nourished solely on organic feed, and allowed to graze freely. Finally, processed foods labeled organic must contain at least 95% certified organic ingredients (discounting water and salt); the remaining 5% of ingredients—items like cornstarch, gelatin, and dairy cultures—must be produced without GMOs, ionizing radiation, or sewage sludge.

USDA organics factsheet

Is It Really Organic?

Despite the detailed, complex requirements of organic classification, not all “organics” are created—or produced—equal. The USDA relies on accredited certifying agents to approve organic farms. Annual farm audits largely entail inspection of paperwork and a visit to the farm. Only 5% of the time do certifiers physically test soil and farm products for prohibited substances. Infrequent testing leaves room for violation—whether accidental or deliberate—and calls into question the reliability of the organic seal.

Certifying agents also have a conflict of interest—they compete with one another to certify farms and receive payment from the farmers they inspect. If inspectors fail a farm, that farm will not apply for organic status next year—representing a future loss of money—and other farms might hesitate to enlist the strict certifier’s services. Such a system incentivizes leniency. According to a Wall Street Journal study, almost 50% of certifying agents did not enforce rudimentary USDA requirements one or more times between 2005 and 2014, while the USDA deemed inspections of two in five certifiers insufficient in that period

Finally, many organic products are imported. Nominally, these items are held to USDA standards, but many are skeptical of overseas inspections by non-US certifiers. Furthermore, complex global supply chains allow much opportunity for mistakes and fabrication.

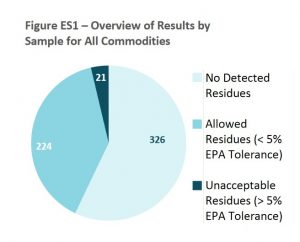

Nevertheless, known organic violations are relatively rare. For instance, a USDA study in 2010-2011 tested 571 organic fruit and vegetable samples for residue of 200 nonorganic pesticides. Although the study was limited in scope, results were encouraging: only 4% of samples violated pesticide residue limits, while 57% contained no traces of pesticides whatsoever.

Pesticide residues on organic food samples in 2010-11 USDA study

Human and Environmental Health

Consumers pay a premium for organics, which are often marketed as safer and more wholesome than conventionally produced foods. However, the health and safety benefits are uncertain. Nutrient levels of organic produce are nearly identical to those of their conventionally-grown counterparts. “I don’t see any nutritional reasons to choose organic foods over conventional,” says one Harvard-affiliated nutritionist. Distance from farm to market, time between harvest and consumption, and preparation style may be more crucial considerations for nutrition-conscious consumers.

Organic foods also contain lower levels of pesticides. All pesticides are toxic, yet there is little evidence that trace amounts of pesticides harm consumers. Furthermore, the safety of permissible organic pesticides compared with conventional pesticides is uncertain. Consumers concerned with farm worker safety must be aware that all pesticides carry a risk. Typically, organic pesticides have lower chronic and acute toxicity levels than restricted use pesticides. However, long-term exposure or improper handling, even of organic pesticides, can harm farm workers’ health, while training and protective gear can shield workers from the detriments of both synthetic and organic pesticides.

Organic farming also impacts environmental health, for better or worse. According to the UN, organic practices maintain biodiversity, sequester carbon in the soil, reduce groundwater pollution, and improve soil health. However, experts believe some organic methods are more harmful than conventional methods. Recently, scientists called out South Dakota’s Gunsmoke Farms, which transitioned from conventional to organic farming, for harming soil health. Rather than using chemical pesticides to target weeds, Gunsmoke Farms tilled the fields and disturbed fragile soil. Overall, organic and conventional farming both have their merits. In some areas—such as energy use—organic farming is greener than conventional farming, while in other areas—like land use—conventional farming is the clear winner.

Markets and Investment

Despite the uncertain benefits of organics, demand is sustained and the market is growing. In 2018, the value of the organic market surpassed $50 billion. Supply and demand levels, too, are favorable for investors: 5.7% of the food market is organic, while just 0.9% of farmland is organic. Prices reflect this trend: a recent National Retail Report found that consumers generally pay significant double-digit premiums—surpassing 200% on certain products—for organics.

As demand continues to outstrip supply and organics fetch high prices, market-wise investors are looking to cash in on the trend. Natural food manufacturers and grocery stores, such as Hain Celestial and Whole Foods (owned by Amazon), provide opportunity for traditional investment. Perhaps the most interesting opportunity from a risk-adjusted return basis on the “healthy eating” theme is United Natural Foods (UNFI), a natural and organic food distributor supplying stores including Whole Foods and Roundy’s Supermarket. UNFI is trading at a very modest 9 times forward Price-to-Earnings ratio and 1.6 times its book value. Investors can also consider large grocery chains, like Costco and Walmart, with their own organic store brands.

The organic market also abounds with alternative investment opportunities. Groups like Farmland LP and SLM Partners are investing directly in the land by converting farms from conventional to organic. The three-year transition period required by the USDA challenges many small farmers, who input much time and money into their land but are unable to market their food as organic during this time. Farmland LP and similar organizations, however, support farmers during this transition. When their products are classified as organic three years later, farmers ultimately reap higher profits.

Many farmers and farmland investors will not stop with organic certification. They will continue to guide organic and more sustainable farm management practices with innovative, environmentally-conscious methods, like improved irrigation and crop rotation. These practices aim to maximize soil and crop health, an endeavor from which farmers, consumers, and investors all can benefit.

To learn more about investing in organics and other “farm to future” themes, contact Servant Financial today.